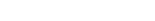

China Hastens the World Toward an Electric-Car Future

Keith Bradsher / New York Times / Oct. 9, 2017

SHENZHEN, China — There is a powerful reason that automakers worldwide are speeding up their efforts to develop electric vehicles — and that reason is China.

Propelled by vast amounts of government money and visions of dominating next-generation technologies, China has become the world’s biggest supporter of electric cars. That is forcing automakers from Detroit to Yokohama and Seoul to Stuttgart to pick up the pace of transformation or risk being left behind in the world’s largest car market. Beijing has already called for one out of every five cars sold in China to run on alternative fuel by 2025. Last month, China issued new rules that would require the world’s carmakers to sell more alternative-energy cars here if they wanted to continue selling regular ones. A Chinese official recently said the country would eventually do away with the internal combustion engine in new cars.

“We are seeing ourselves at a crossroads in the development of the automobile industry in this country, with a global scale in mind,” said Jürgen Stackmann, Volkswagen’s top executive for VW brand sales and marketing, during a visit to Shanghai.

China has reshaped industries before — clothing, steel making, even lace — through a potent mix of government support and cheap labor. More recently it has transformed green-energy businesses like solar and wind power.

This, however, would be on a different scale.

If China succeeds — and there is no guarantee — Beijing’s policy makers will be front and center reimagining the global auto industry, a business that has helped define communities, industries and people’s aspirations for more than a century. It is a role that was almost inconceivable just a few decades ago, when China was more closely associated with a different type of green transportation: the black, classic Flying Pigeon bicycle.

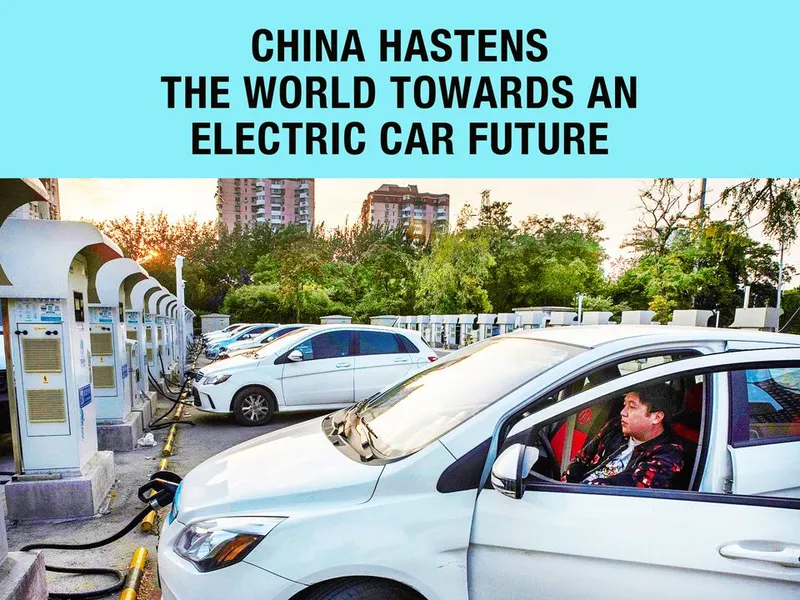

China feels it has little choice in pressing forward. While it is true that electric vehicles fit neatly into China’s plan to become the world leader in sci-fi technology like artificial intelligence, the country also fears a dark future — one where its cities remain cloaked in smog and it is beholden to foreign countries to sell it the oil it needs. Already, China is the world’s largest maker and seller of electric cars. Chinese buyers are on track to snap up almost 300,000 of them this year, three times the number expected to be sold in the United States and more than the rest of the world combined.

The country’s market heft is considerable. China buys more General Motors-branded cars than Americans do. Even for Tesla, the still-small American maker of luxury electric sedans, China has become the second-largest market, even though China’s taxes on imported cars are 10 times as high as those in the United States. Tesla officials have said they are considering opening a factory in China.

A week ago, G.M. and Ford unveiled plans to add a combined 33 electric models to their lineups. Global manufacturers like G.M. and Volkswagen are also moving much of their research, development and production of electric cars to China. China in turn is pressuring them to share that technology with their Chinese partners.

Behind the scenes, China is recruiting some of the world’s best electrical engineering talent, even in the United States. China is also home to many smaller companies that make the parts essential to assembling electric cars. All this comes just as electric cars are finally starting to become competitive with gasoline- or diesel-powered cars on performance and cost. Electric cars are an increasingly common sight in cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. For some drivers here, electric cars are all they know. “I don’t plan to buy a gasoline car, since I heard they are going to be banned for sale,” said Xiong Jianghuai, a lawyer based in Shanghai, who has bought two made by Chery, a Chinese automaker. He said he was delighted that the operating cost was less than one-fifth of the cost of buying gasoline, even if the initial purchase price was a little higher. “I think the future lies in electric cars,” Mr. Xiong said.

Many outside China — including some members of President Trump’s administration — say China is using unfair government support to create national champions that could eclipse their rivals abroad.

Chinese auto executives say their country is pursuing common-sense policies to develop cutting-edge industries.

“In China, the entrepreneurs in the industrial sector are very lucky, because we have the foundation” from the government, said Li Bin, the founder and chairman of the NIO Company, a Chinese electric car manufacturer. “These opportunities are rare or impossible in any other country in the world.”

China’s ability to dominate electric cars is not ensured. China’s auto manufacturing skills are considerable, but it has yet to create a single car model that has become popular abroad Even in China, most car buyers still prefer Fords, Chevrolets and Volkswagens largely made by government-mandated joint ventures between global and Chinese companies. When it comes to electric cars, most Chinese models are inexpensive and boxy, unlike the sleek lines and looming falcon-wing doors of Tesla’s latest models.

Chinese officials have long called for electric cars to be practical, and not just luxuries.

“The central government has made a lot of strategies for the development of new energy vehicles,” said Song Qiuling, a deputy director at China’s Finance Ministry. “That is why we have seen the progress and development of new energy vehicles.”

Some players have already stumbled. Faraday Future, an electric car company based in the United States but owned by a Chinese company, scaled back after its parent hit hard financial times. China yanked electric-car subsidies away from a number of local companies after an investigation last year showed that many were overstating sales. The environmental benefits may be tough to realize any time soon. Nearly three-quarters of China’s power comes from coal, which emits more climate-changing gases than oil. Even on electricity, China’s cars are still burning dirty.

China is also favoring battery electric technology that it can call its own. Foreign automakers already control much of the advanced technology behind fuel-sipping alternatives such as plug-in hybrids, like the Toyota Prius, which runs on both gasoline power and an electric battery.

Still, electric cars make particular sense in China. China’s dense and crowded cities often mean shorter driving distances, while its extensive high-speed rail system reduces the need for long-distance road trips.

Han Tao discovered the limits of electric cars the hard way. A 35-year-old stock investor in Beijing, he said he ran out of charge in July while driving to Shenzhen, 1,300 miles away. His Chinese-made BYD E6 electric sedan needed a tow.

Still, he said, he and his wife prefer the E6 over the gasoline-powered Chevrolet Cruze they bought four years earlier.

“It doesn’t have the oily smell and the noise from the engine,” Mr. Han said. “It accelerates way faster than gasoline cars. It feels like you are on a high-speed train.”

China’s push for electric cars shows how its industrial ambitions can endure big political shifts. China named a former Audi engineer, Wan Gang, its minister of science and technology in 2007, and he has kept the position and maintained the push despite the emergence of a new slate of Chinese leaders.

Wen Jiabao, China’s second-most-powerful official as premier from 2002-12, was an avid supporter of electric cars who came from Tianjin, the center of China’s battery industry. Mr. Wen’s successor as premier, Li Keqiang, has also turned government backing for high-tech industries into his signature accomplishment, while President Xi Jinping has strongly endorsed the effort. “The development of new energy vehicles,” said Xu Chaoqian, a top aide to Mr. Wan, “has received a lot of support from President Xi, Premier Li and others.”

Recent Posts

- The 2022 Audi Q4 e-Tron SUV combines performance, practicality and luxury

- Ford's 2022 F150 Lightning All-Electric Truck is in high demand

- Legendary Audi performance is at the heart of the 2022 Audi e-tron GT and its RS sibling.

- Meet the Lexus RZ 450e – the luxury brand’s 1st EV

- The 2022 GV60 is Genesis’ first all-electric vehicle